In the past decade, the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation has become the most influential supporter of research on IUDs and expanding access to the contraceptive

Katherine O’Reilly, a certified nurse midwife in her 30s, works full time at the Mesa County Health Department’s clinic in Grand Junction, Colo., and she’s eager to show off the clinic’s stash of one of the most effective forms of birth control. First, though, she has to get out her electronic badge to unlock a heavy wood door with a paper sign, “PLEASE KEEP DOOR CLOSED AT ALL TIMES!!!” She surveys shelves packed with boxes of gloves and gauze, then walks over to an unmarked metal cabinet. She opens it and bends down to look at the bottom shelves. “There they are!” she says, as if they’d been hiding from her.

She points to a stack of long, slim packages the size of a box of chocolates. Inside each is an intrauterine device and a tall, skinny straw that clinicians use to insert the flexible, T-shaped pieces of plastic into a uterus, where it can prevent pregnancy for as long as 10 years. “When I see patients, my goal is to be able to initiate contraception today,” she says.

That means having IUDs in stock is essential.

It’s also expensive. IUDs can retail for more than $800 each, so a public health clinic such as Mesa County’s that attends to women with little or no medical insurance treats the devices almost like a controlled substance. The clinic spends $774,000 a year to serve a rural county of some 150,000. It can stock the pricey devices thanks in part to a statewide initiative to reduce unplanned pregnancies. The $24 million for the six-year effort came from an anonymous donor.

That funding ended in July. Luckily, O’Reilly says, there’s now a lower-cost alternative. This summer, the clinic got its first shipment of an IUD named Liletta that hit the market in April. Liletta is manufactured and sold by Allergan but was developed by a nonprofit, Medicines360, whose entire seed funding—$74 million—also came from an anonymous donor. “Our clinic can get Lilettas for $50,” O’Reilly says. “With our population, once we get that going, Liletta will be the one most women choose.”

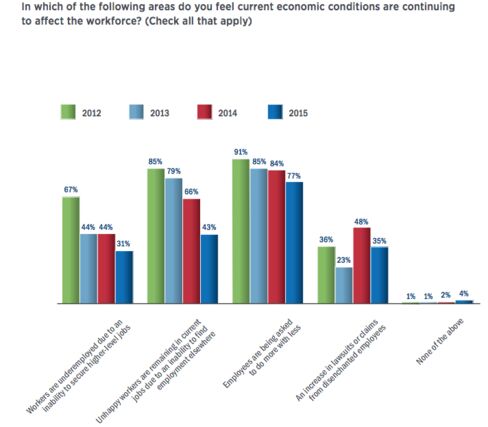

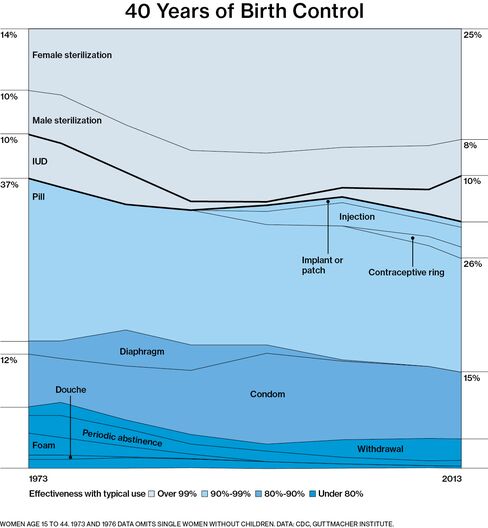

A decade ago, almost no one in the U.S. had IUDs because of the device’s awful history and lingering reputation. By 2013, however, as women learned about superior, safer designs, IUDs had become the method of choice (PDF) for more than 10 percent of women using contraceptives, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among women age 25 to 34, they’re as popular as condoms, and they’re far more effective. The U.S. contraceptive market, including pills and IUDs, totaled more than $6 billion in 2013, according to Transparency Market Research.

A multiyear study of almost 10,000 women in St. Louis found that when providers offered women all forms of contraception for free, 75 percent chose IUDs and hormonal implants. The study’s been cited by several medical groups, including the CDC as part of its recommendation to doctors to encourage IUD use. This study received close to $20 million, also from an anonymous donor.

Almost all women—and therefore men—use a form of birth control at some point in their lives, yet contraception is so politically and legally radioactive that legislators and pharmaceutical companies avoid funding it. So it’s no coincidence that the money behind the Colorado initiative, the St. Louis study, and Liletta all came from an unnamed philanthropic source—they all were from the same discreet foundation. Very few people will discuss The Anonymous Donor on the record, but tax filings, medical journal disclosures, and an archived interview with a foundation official show the funds come from Warren Buffett, the chairman and chief executive officer of Berkshire Hathaway, and his family.

“You can’t send out a press release, and you can’t talk about,

‘We got Buffett money’ ”

Named for Buffett’s first wife, the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation is the third-largest family foundation in the country, behind only the Bill & Melinda Gates and Ford foundations. In 2013, the most recent year for which tax filings are available, it gave away almost half a billion dollars, largely to organizations dedicated to reproductive health. It barely maintains a website, studiously avoids press, and has about 20 people on staff. The foundation and Buffett didn’t respond to requests to comment for this article.

But in a January 2008 interview for a reproductive health oral history project that hasn’t previously been made public, Judith DeSarno, the Buffett Foundation’s former director for domestic programs, was candid about the foundation’s giving.

“Buffett alone will give more than all of the other foundations combined in reproductive health,” she said. “We already are this year, and that will continue.” DeSarno declined to comment for this article, other than to say, “I am incredibly proud of this work and the dramatic decrease in unintended pregnancies.”

In the past decade, the Buffett Foundation has become, by far, the most influential supporter of research on IUDs and expanding access to the contraceptive. “This is common-sense, positive work to help families meet their dreams and their needs in planning their pregnancies,” says Brandy Mitchell, a nurse practitioner who coordinates family planning at Denver Health, a state-run provider. “Why we have to rely on a donor to make this happen is beyond belief.”

Quietly, steadily, the Buffett family is funding the biggest shift in birth control in a generation. “For Warren, it’s economic. He thinks that unless women can control their fertility—and that it’s basically their right to control their fertility—that you are sort of wasting more than half of the brainpower in the United States,” DeSarno said about Buffett’s funding of reproductive health in the 2008 interview. “Well, not just the United States. Worldwide.”

Distrust of IUDs dates to 1971, when A.H. Robins Co. started marketing an IUD called the Dalkon Shield. It was a circular piece of plastic resembling a crustacean with 10 little arms. More than a dozen other such devices were on the market in the 1970s, in part because the government didn’t regulate IUDs. “You could make your IUD in your garage,” says Eve Espey, a doctor who helped write IUD guidelines for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

With aggressive marketing, the Dalkon Shield quickly became the most popular IUD in the U.S., selling more than 2 million devices in three years. But soon horrific problems arose. All IUDs have a short string that’s used to eventually remove the device, but the design of the Dalkon Shield’s string drew bacteria into the uterus, causing infections that made some women infertile and have ectopic pregnancies. Several women died. In 1974, A.H. Robins, hit with what would total $12 billion in lawsuits, discontinued the Dalkon Shield. After that, almost no one would touch IUDs, pharmaceutical companies especially. For almost two decades, medical guidelines cautioned against them, stipulating their use mainly for older women who smoked so much it interfered with the effectiveness of the pill.

The Dalkon Shield fiasco propelled the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to gain oversight of medical devices, and in 1984 it approved the Paragard (PDF), a copper IUD developed by the Population Council, a nonprofit whose funders have included the Buffett Foundation. But the Paragard never gained mass appeal, and for more than a decade, medical research into IUDs all but stopped.

At least in the U.S. In Europe, research indicated that well-designed devices didn’t increase the risks of infections or infertility. Oddly, the research was less conclusive on how, exactly, IUDs prevent pregnancy. They make the uterus inhospitable to sperm, so maybe that’s it. Some also act to thicken the walls of the cervix, which reduces the space for sperm to wiggle into the uterus. IUDs may also make it hard for a fertilized egg to attach to the uterine lining. And, unlike the pill, they don’t require daily maintenance, which reduces the risk of user error. Whatever the combination of reasons, IUDs are 99 percent effective in preventing pregnancies, making them as effective as sterilization.

In late 2000 the FDA approved another IUD, Mirena, which emits a synthetic hormone. It was also developed by the Population Council. Its label allowed use by women who’d already had a child, and Bayer eventually owned the distribution rights. In 2002, fewer than 2 percent of American women used IUDs. But that was about to change.

Warren Buffett met Susan Thompson through his sister, who was Thompson’s college roommate. The two married in 1952 and lived in their hometown of Omaha for more than two decades, during which Buffett bought and began building Berkshire Hathaway into one of the largest companies in the world.

Susan was a cabaret singer and passionate about women’s rights. In the 1960s, the couple set up what was then called the Buffett Foundation, which focused on nuclear disarmament and reproductive health, including helping to fund Planned Parenthood as well as the development of RU-486, the so-called abortion pill. In the late ’70s, the duo entered into an unusual arrangement—they remained married, but Susan moved to San Francisco. She also introduced Warren to the woman who would become his longtime companion, Astrid Menks, whom he married decades later after Susan’s death.

Susan and Warren’s daughter, Susie, moved to Omaha from Washington, D.C., in the mid-1980s, and her then-husband, Allen Greenberg, started running the foundation’s day-to-day operations in 1987. (Now divorced, the two work together at the foundation.) It’s housed in the same downtown mid-rise as Berkshire Hathaway. In its fiscal year ended June 2002, it gave away $33.4 million. Then, a series of events changed its giving exponentially.

For years, Berkshire’s stockholders could designate a recipient for their share of the company’s corporate philanthropy. Buffett and Susan often allocated their sizable portion to the foundation. Anti-abortion activists weren’t pleased, but it wasn’t until the early 2000s that the donations became a liability. In 2002, Berkshire acquired Pampered Chef, which sold kitchenware through a direct sales model akin to Tupperware parties. Pampered Chef brought Berkshire into the living rooms of homemakers in Middle America, opening a vulnerability anti-abortion activists exploited. After protesters called for a boycott, Pampered Chef’s founder, Doris Christopher, appealed to Buffett.

“I thought we could tough it through, but we can’t,” Buffett told biographer Alice Schroeder for her 2008 book, The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life. He said he felt Pampered Chef’s saleswomen were at risk of losing business. “It hurts Doris, and these are her flock. They’re getting injured.” Schroeder went on to write, “He didn’t say it, but implicitly, not just their livelihoods but their physical welfare was at stake.”

The Pampered Chef clash forged a line between what Buffett, investor and employer of hundreds of thousands, would tolerate and what Buffett, the individual, could endure. “When it’s his own view—it’s his own money—who cares what you think?” says Jeff Matthews, an investor who’s written several books on the company. “He is not going to change his own personal behavior.” Berkshire ended its shareholder corporate-donation program in 2003. But Buffett kept on giving from his personal wealth.

In 2004, Susan died of a stroke at age 72, leaving about $2.5 billion of her estate to the foundation, which was renamed after her. The foundation’s board reorganized. Buffett relinquished his seat, and Susie became board chairman. Buffett later said he’d always assumed his wife would outlive him and be the one “who oversaw the distribution of our wealth to society.” Her death forced him to reassess his plans for the more than $40 billion in Berkshire stock he held at the time.

In 2006, Buffett announced his decision in a cover story of Fortune (PDF), pledging to eventually donate 85 percent of his Berkshire stock, valued then at $37 billion, to philanthropic causes. He committed the bulk to the Gates Foundation, with the remainder going to the three foundations run by his children and a million shares, then worth more than $3 billion, promised to the Buffett Foundation. According to tax and regulatory filings, since 2006 Buffett has given $1.7 billion of his Berkshire shares to the foundation. Almost 60 percent of the original bequest, now worth roughly $4.2 billion, remains pledged to be transferred to the foundation over the coming decades.

Foundations must spend at least 5 percent of their assets each year, so the new influx from both Susan and Warren forced the foundation to expand quickly. In September 2006 it hired DeSarno, the longtime president and CEO of the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association, a group that represents women’s health clinics that receive federal support. She’d led the group to push for broadening access to low-cost contraception.

In the 2008 interview, DeSarno said Pampered Chef did affect the foundation in at least one way: It continued to fund what it wanted to fund but made anonymity a condition of its bequests. “It has to be as ‘anonymous,’ ” DeSarno said. “You can’t send out a press release, and you can’t talk about, ‘We got Buffett money.’ ”

In 2005 the Buffett Foundation gave away about $60 million globally. In 2007 it donated $79 million in the U.S. alone, DeSarno said in the 2008 interview. “Next year I’m going to give at least $50 million more than I gave this year.”

DeSarno also worried that the foundation’s huge gifts would cause other donors to move their funding to different causes. “That scares me to death, and that really does say, ‘Judy DeSarno gets to figure out what happens in the United States on reproductive health in terms of who gets funded and who doesn’t,’ ” she said.

As the foundation’s spending grew, so did its focus. Earlier, it had concentrated on abortion-related work. Its new spending would expand to include at least $200 million to avoid abortion by building the research, policy, and commercial foundations to promote the rise of IUDs.

The first step involved building better academic, peer-reviewed research on IUDs, particularly looking at the public health effects on teens and women who haven’t had kids. Increasing the medical literature would help win over doctors who remained averse to promoting IUDs to these very women.

“In December 2006, I got a call from an anonymous foundation, and they said they would like to help women use the most effective methods of contraception,” recalls Jeffrey Peipert, a doctor and leading researcher with the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Washington University in St. Louis. “They said, ‘You come up with a program to promote and encourage the use of the most effective methods,’ and I suggested we do a project where we make all contraceptive methods free and see what they choose.” The foundation asked for back-of-an-envelope calculations for a budget, according to an account published by the university’s press office. “He e-mailed the head of the foundation asking for some idea of how many patients he should plan to recruit,” the university reported. “The director told him to ‘THINK BIG! Happy Hanukkah!’”

Peipert says he can’t discuss his benefactor. “We were told in all correspondence and all journal articles, we would list them as the anonymous foundation,” he says. “I’m sure they have good reasons for this, and it probably has to deal with the other things they fund.” Much of the foundation’s other grants go to abortion-related work.

Katherine O’Reilly in the Mesa County Health Department’s medical supply room.

Katherine O’Reilly in the Mesa County Health Department’s medical supply room. Photographer: Morgan Rachel Levy for Bloomberg Businessweek

The New England Journal of Medicine, which requires funding disclosures, reported the Buffett Foundation’s support for the study known as the Contraceptive Choice Project, and tax forms show the foundation gave Washington University about $20 million beginning in 2007, when the study was launched, through 2013. (Peipert says his budget was “not quite” that amount.) The Choice Project remains the biggest U.S. medical study of IUD users conducted.

In August 2007, Peipert and his team began recruiting 9,256 women from across the St. Louis area. About half had never been pregnant, and more than 20 percent were teenagers, some as young as 14. At clinics around the city, researchers counseled the women about all the different types of birth control, with an emphasis on IUDs and implants, offering them all for free. They followed the women for more than three years.

In 2010, Peipert and his colleagues published their early findings in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, reporting that 56 percent of the women chose IUDs, with an additional 11 percent opting for hormonal implants. The findings immediately provided a jolt to the field, making a powerful argument to practitioners and policymakers that women would want IUDs if they knew about them and had access to them. The St. Louis researchers published at least 50 more papers.

The Choice Project has had the kind of wide-ranging impact that donors rarely see. In 2011, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists updated its guidelines for the first time since 2005 to support a broader use of IUDs. It cited the Choice Project findings in the first paragraph. In 2014 the CDC also pointed to the Choice Project (PDF) in its recommendations for practitioners teaching women about birth control options: They should start by introducing the most effective ones, such as IUDs.

Academic research wasn’t enough, though; the foundation wanted to get inside the clinics where women were making birth control choices and ensure they were aware of, and could afford, the most reliable options. So it decided to pick two states and pour resources into them—supporting provider training, social marketing, and lower costs—to change the perception of IUDs and build political support for the devices. The first, ahead of the 2008 presidential primary, was Iowa.

“Allen was hoping we would be up and running … so that presidential candidates would have to comment on access to family planning, not abortion,” DeSarno said in the 2008 oral history. When her assistant first called local family planning clinics, no one had heard of the Buffett Foundation, even though it was already a major donor, DeSarno said. They recognized DeSarno’s name, though, and some people cried when they heard there was money coming their way. Over five years starting in 2007, the Buffett Foundation would spend more than $50 million in the Hawkeye State.

The foundation began making a big push into Colorado, a far larger and more diverse state, in 2008. “They didn’t want some completely blue liberal-leaning state, where people could go, ‘Of course they can do it there because of the politics,’ ” says Greta Klinger, the spokeswoman for the Colorado Initiative to Reduce Unintended Pregnancies, as the effort was known. Klinger acknowledges the Buffetts provided the funding but still generally talks about “the foundation” when discussing it.

Tax filings show that from 2008 to 2013, the Buffett Foundation spent about $50 million in Colorado, with roughly half going directly to the state. The state spent about half of its funds to purchase the devices, so they’d be free. The rest of the state’s funding went to hiring and training clinicians. Mesa County Health Department head Jeff Kuhr says it took several years and almost a complete staff turnover to be able to introduce IUDs. The clinic hired O’Reilly and another nurse midwife who have been trained in counseling and insertion. In 2013 the clinic inserted 101 IUDs and implants; so far this year, it’s inserted 189.

Last year, Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper released results of the initiative, showing the kind of change DeSarno said she’d hoped would persuade policymakers to back family planning. The teen birthrate dropped 40 percent from 2009 to 2013, and the teen abortion rate was down by more than a third. “This initiative has saved Colorado millions of dollars,” Hickenlooper declared.

The teen birthrate dropped 40 percent from 2009 to 2013, and the teen abortion rate was down by more than a third

This spring, when the legislature debated taking over the funding after the Buffett donation ran out, conservative legislators voted against providing support, saying the efforts amounted to mini abortions—and anyway, private donors could fund it. The state is now soliciting other foundations, but even without additional funding the initiative may have lasting effects. “A couple of years ago, there wasn’t a lot of interest from outside providers,” says Klinger. “I think that’s shifting. We have hit a critical point in the state that people are saying, ‘Oh, oh, there really is a demand for this.’ ” With minds changed, the remaining barrier is the cost of IUDs themselves. The Buffetts have a fix for that, too.

“You know, it’s worth taking a look at getting a generic IUD,” DeSarno mused in the 2008 interview. “People can’t get it at a good price.” Now, seven years later, a good price is just what the Buffett Foundation has achieved. This April, Liletta, the low-cost IUD, became available. Its design isn’t revolutionary, but its business model is.

From the beginning, the aim for Liletta was a product that would cost public clinics just $50 and wouldn’t require foundation funding in perpetuity. In 2008 the foundation hired Victoria Hale as a consultant, according to tax filings. The following year, Hale, a MacArthur Genius Grant recipient, founded Medicines360.

The patent for the Mirena, which Bayer distributes and retails for as much as $800, expires later this year, so Medicines360 could have waited and made a knockoff for cheap. But at the time, the FDA didn’t have a way to approve a generic IUD, according to David Turok, a gynecologist at the University of Utah who worked on Liletta’s clinical trial. Merely selling a low-cost device also wouldn’t guarantee Medicines360 could generate enough revenue to support itself. “The initial funder said, ‘Look, I will fund the R&D, the full ride to approval, but then you have to be self-sustaining,’ ” says Pamela Weir, Medicines360’s chief operating officer.

The Liletta IUD.

The Liletta IUD. Photographer: Brea Souders for Bloomberg Businessweek

So Medicines360 developed a hormonal IUD almost identical to Mirena. The idea was for the nonprofit to partner with a company that would sell it at market rates for people with good insurance, essentially subsidizing the low prices for the public sector. For the nonprofit to have a branded product whose distribution rights it could sell, Medicines360 needed a clinical trial, Turok says. Most drug trials are as small as necessary to get approval, but Medicines360 designed an expansive trial to broaden access, hoping the IUD’s official FDA label would show that nearly all women of childbearing age could safely use the device.

It signed up 1,751 women age 16 to 46. The multiyear study found Liletta to be 99.45 percent effective in preventing pregnancy, regardless of factors such as age and weight. This February, Medicines360 and the Buffett Foundation got what they wanted. The FDA approved Liletta (PDF) for use of up to three years, saying it’s safe for almost any woman, with a few exceptions, such as if she’s pregnant or has acute pelvic inflammatory disease.

Jessica Grossman, who recently replaced Hale as CEO, says she can’t discuss the funding source, yet according to the Buffett Foundation’s tax filings, it’s given more than $74 million to Medicines360. “All we can say is that we had an anonymous donor,” Grossman says. “I wish I could be more helpful, because I know it’s a fascinating story.”

Allergan sells Liletta for slightly less than what Mirena costs, but, as the foundation required, public clinics pay only $50. Allergan agreed to pay Medicines360 $50 million upfront, plus as much as $125 million more in addition to royalties. Grossman says Medicines360 is using the proceeds to develop new products for women and keep the Liletta trial running in the expectation of getting FDA approval for using the device up to seven years.

The Buffetts’ strategies have been so successful in building the medical, policy, and market infrastructure for IUDs that even proponents have begun to worry enthusiasm has gone too far. While IUDs produce great results from a public health perspective—and, as the Choice study found, women tend to be happy with them—there are many reasons for a woman to choose other contraception, they say. She may like how the pill reduces her acne, how a condom protects against sexually transmitted diseases, or how she can simply stop using other methods, rather than having to go to a clinic to have an IUD removed.

Rachel Benson Gold, a longtime researcher at the Guttmacher Institute, which receives Buffett support, published a paper last summer arguing that policymakers need a “delicate balance” between making IUDs accessible and ensuring women aren’t coerced into using them, particularly since so many efforts target low-income women.

There are reasons Gold and others might be nervous. This March, a state legislator in Arkansas proposed a bill that would pay unwed, low-income mothers on Medicaid $2,500 to get an IUD. That echoes a not-so-distant controversy over the Norplant hormonal implant.

After it hit the market in 1991, legislators in more than a dozen states introduced bills that would have pushed women into getting the implant as a condition of welfare, in lieu of jail time, or in exchange for cash. The Norplant inventor expressed horror that women could be coerced into using a contraceptive he’d designed to help them gain control of their own fertility—and future.

If more policymakers try to contort the effectiveness of IUDs into a tool for social engineering or make its use a condition for state support, the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation may find itself needing to fund yet another battle—to ensure that a woman not only has access to an IUD, but that it is her choice to get one.