Move to allow the market a greater say in setting the yuan level is roiling currencies, commodities and stocks the world over

The steepest slide in the yuan in two decades is a game changer. The last time the currency moved this much -- 1994 -- China's economy ranked as the world's eighth largest, just behind Canada's, and few outside its borders would have even been able to put a name to the currency.

Now, the nation's move to allow the market a greater say in setting the yuan level is roiling currencies, commodities and stocks the world over and reshaping the global economic outlook.

Here are a few ways a sustained yuan downturn will be felt:

Can the Fed still lift off if the greenback keeps strengthening? Bank of America Merrill Lynch analysts are among those who think the yuan devaluation clouds the picture for Janet Yellen.

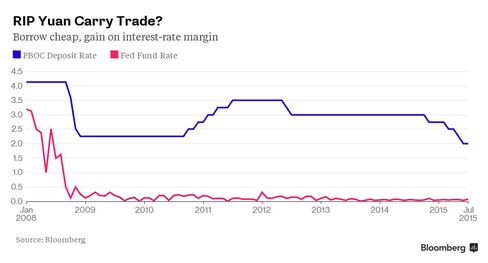

It was like money for jam -- borrow cheaply offshore, somehow get the funds to China to earn a hefty interest-rate margin, and sell out later with a currency gain to boot. A sustained yuan downturn would kill the carry trade.

Even putting aside a weaker yuan, deepening factory-gate deflation and the likely spillover to export prices spelled cheaper toys, T-shirts and television sets across the world. Now add in the weaker currency and we could see China's devaluation revive deflation fears globally.

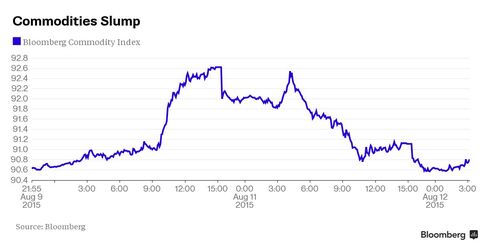

Global commodity prices -- mostly still priced in U.S. dollars -- have been whacked since the yuan move. More weakness would bode ill for economic prospects in dependent nations including Australia, Brazil and Chile.

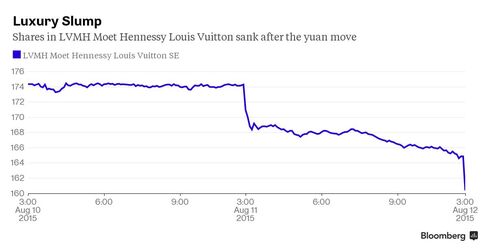

A weaker yuan also means it's more expensive now for Chinese consumers to buy German cars, Swiss watches and French handbags. That's bad news for a region mired in it its own gloomy outlook, especially if Chinese tourists cut back on their overseas vacations.

Asian stocks tumbled. Japan's Topix Index could fall 5 percent to 10 percent if the yuan depreciates more than 10 percent, according to BofA.

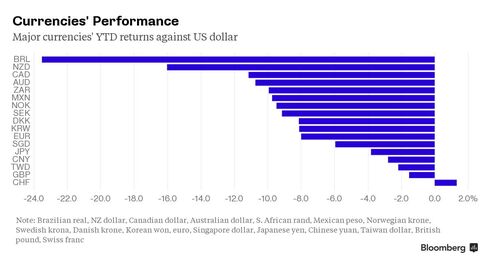

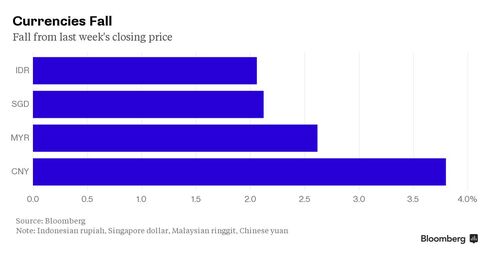

Yuan weakness is spurring selling of other regional currencies. Already, Vietnam has responded by widening the dong's trading band. Could other central banks be forced into defensive moves?

Of course, there is a bright side: if a weaker yuan helps China regain its mojo, that's a plus for the global economy.

No comments:

Post a Comment