In 2012 Jeff Bezos scooped up warehouse automation firm Kiva. Everyone else is still trying to catch up.

An Amazon warehouse is a flurry of activity. Workers jog around a manmade cavern plopping items into yellow and black crates. Towering hydraulic arms lift heavy boxes toward the rafters. And an army of stubby orange robots slide along the floor like giant, sentient hockey pucks, piled high with towers of consumer gratification ranging from bestsellers to kitchenware.

Those are Kiva robots, once the marvel of warehouses everywhere. Amazon whipped out its wallet and threw down $775 million to purchase these robot legions in 2012. The acquisition effectively gave Jeff Bezos, its 52-year-old chief executive, command of an entire industry. He decided to use the robots for Amazon and Amazon alone, ending the sale of Kiva's products to warehouse operators and retailers that had come to rely on them. As contracts expired, they had to find other options to keep up with an ever-increasing consumer need for speed. The only problem was that there were no other options. Kiva was pretty much it.

It's taken four years, but a handful of startups are finally ready to replace Kiva and equip the world's warehouses with new robotics. Amazon's Kiva bots proved this kind of automation is more efficient than an all-human workforce. The new robots being rolled out look different, partly because the industry is still experimenting and partly because of patent issues. Some focus on picking items off shelves, others zoom around with touch screens. All are aimed at saving retailers money as they race to get their wares to your doorstep as quickly as possible.

Amazon has about 30,000 Kiva robots scuttling about its warehouses across the globe. Dave Clark, the retailer's senior vice president of worldwide operations and customer service, estimated the addition of the bots reduced operating expenses by about 20 percent. According to an analysis by Deutsche Bank, adding them to one new warehouse saves $22 million in fulfillment expenses. Bringing the Kivas to the 100 or so distribution centers that still haven't implemented the tech would save Amazon a further $2.5 billion.

“To be great in e-commerce, you need to be sophisticated inside the warehouse,” said Karl Siebrecht, chief executive at Flexe, which bills itself as the Airbnb for warehouse space. Amazon was the first company to confront the challenge of picking a virtually endless variety of goods from warehouse shelves and combining them in a single box for home delivery. Now that e-commerce is a growing part of the retail trade, more companies are paying attention. “The case for automation is building across the industry,” Siebrecht said.

But it's really only Amazon that has this kind of technology at scale, thanks in large part to Kiva. The world's biggest retailers, including Wal-Mart Stores Inc., Macy's Inc., and Target Corp., have yet to populate their warehouses with widespread robotic systems.

They rely on the old method—otherwise known as humans: Hordes of pickers and packers who send boxes down conveyor belts.

For the new breed of robot makers, the potential market is wide open. Logistics companies that run their own warehouses started designing automatons while ambitious engineers saw the hole Bezos blew in the market and jumped in. One startup was even founded by former Kiva employees. The race to automate was on.

Saving money on parking lots

The modern warehouse is a rectangular box with 40-foot high ceilings, loading docks on both sides, and often, thousands of parking spaces for staff that swells during peak shopping seasons. Lately retailers have been demanding something new: floors that approach the Platonic ideal of flatness, a feature that makes life easier for the technologists managing fleets of warehouse robots.

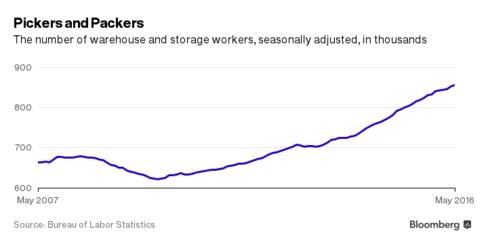

While automation has long been the looming threat to industrial workers, there's reason to think their situation is about to become worse. There were 856,000 warehouse workers in May, according to seasonally-adjusted data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The average wage for those workers is about $12 an hour, said David Egan, head of industrial research for the Americas at commercial real estate firm CBRE Group. Minimum wage hikes being considered and enacted nationwide could drive labor costs higher, especially in locations close to city centers—sites that are in high demand as retailers chase Amazon into the realm of same-day delivery.

Investing in automated distribution centers may offer companies a hedge against such uncertainty, though it will come at the expense of an increasing number of Americans who rely on warehouse work to survive. Not only could robots pare labor costs over the long term, they may protect employers against labor shortages, a particularly scary proposition for the biggest retailers come Christmas time. Robots can help improve speed and accuracy and increase productivity per square foot of warehouse space at a time when the growth of e-commerce is driving up commercial rents.

All these imperatives have led most big warehouse users to experiment with new types of automation. “Some companies are implementing in a big way, and the majority are doing at least a pilot project on one small area or in one warehouse building,” said Raj Kumar, a partner at consulting firm AT Kearney. That includes Walmart, which has been using robots to ship apparel from its e-commerce website, he said. Walmart, which didn't respond to an email requesting comment, has also been experimenting with flying drones that photograph warehouse shelves as part of an effort to reduce the time it takes to catalogue inventory.

"Warehouses are very high tech places," said Bruce Welty, co-founder and chairman of Locus Robotics, a firm that's developed bots to work alongside, rather than replace, human workers. "Because the only way you can take costs out is automation."

A warehouse robot from Locus Robotics

Amazon takes its marbles and goes home

Locus is a spinoff of a company called Quiet Logistics, which owns two warehouses in Massachusetts, a gateway of sorts for e-commerce goods being distributed across America's northeast corridor. Welty and his co-founders based their distribution business on Kiva's robots. They built software systems around the Kiva bots to improve efficiency as they moved goods for such retailers as Zara, Gilt, and Bonobos. Then Amazon blew it all up.

"I said once to my board—casually, almost as a joke, 'Boy, we’d really be screwed if Amazon bought this company,'" said Welty. "But I never really thought this would happen." Such a move was unprecedented in warehousing: the mass withdrawal of one specific type of technology. Usually, one company would buy another and keep selling the tech to all the usual customers. That's where the money was, after all. Not Amazon. It wanted the Kivas all for itself.

Amazon declined to comment.

So in early 2014, Quiet Logistics decided to take the leap. Instead of using someone else's technology, it would develop its own. Welty hired a team of roboticists and engineers. Within a year, they had a prototype. Within two years, Locus was up and running, and then spun off into its own company. In May, it raised $8 million in venture capital funding. Thus far, Locus robots can only be found humming along the corridors of Quiet Logistics warehouses, but the company says it signed on with three major retailers for pilot projects that may start by summer's end. It also said it plans to add up to a dozen warehouses over the next year.

Locus's robotic minions are much smaller than their Kiva counterparts. A stand shoots up from the Locus robot's circular base with a platform to place bins full of goods. A touch screen is mounted at chest-level, like a podium on wheels, so the bot can tell workers what it needs. Rather than haul around entire pods of merchandise, the Locus bots scurry to warehouse workers and prompt them with a touchscreen. Human workers, each in charge of a particular zone, retrieve the items and give them to the robots, which then move on to the next spot. Laborers won't get exhausted from walking miles each day, and the warehouse isn't limited by the A-to-B nature of conveyor belts. Perhaps it's an example of humans and bots working in perfect harmony.

Fetch Robotics, based in San Jose, makes a warehouse robot that follows workers around, catching the items they pick off the shelves. Harvest Automation, based in Billerica, Mass., sells a similar version. There are also European companies that specialized in earlier generations of warehouse automation, often revolving around conveyor belts and systems that moved goods along track-mounted shuttles. While many of the new systems focus on moving stuff around, a whole generation of robots is trying to automate the picking process—grabbing items off shelves—through more dexterous methods. There's Toru, a bot from German firm Magazino that can grab individual items, for example. And 6 River Systems, a Boston-based startup founded by some former Kiva executives, is currently running pilot programs for new, as-yet-undisclosed products.

"It's a perfect storm of opportunity," said Welty of the onslaught of competition. "Kiva paved the way, but it only got us partially there."

Next step: Automated drones

Amazon seems to realize that. As other warehouses become more efficient, so must Amazon's. At its robotics lab in an industrial complex carved out of the woods in North Reading, Mass., surrounded by electronics and biopharmaceutical firms in the state's tech-firm heartland, Amazon is working on all sorts of automation in the hopes of cutting costs and speeding fulfillment. Alongside the Kivas, Amazon is working on automated drones as well. And those are just the robots it's revealed to the public.

"I have as no idea if this is as far as Amazon wants to take it," said Jason Helfstein, an analyst at Oppenheimer & Co. "Do you get into autonomous vehicles? Self-driving trucks?"

In March, robotics companies flocked to a California resort for a secret conference hosted by Amazon. Over three sweltering days at the Parker Palm Springs, attendees were treated to talks and seminars on everything from artificial intelligence to space exploration. Representatives from Intel Corp. and Toyota Motor Corp., roboticists from all sorts of firms, and academics from nearby University of California-Berkeley and far away Zurich showed up. So did Bezos, who sipped single-malt whiskey, chatted with guests, and hit the conference stage wearing a robotic suit. Ron Howard, the film director (whose portfolio includes the 1995 docudrama Apollo 13), made an appearance. Robo-arms dueled with Star Wars lightsabers. Amazon served grapes and drinks on tables mounted atop bright orange Kivas.

Guests were warned not to share details, and Seattle-based Amazon remains silent about its robot tactics. Executives have said almost nothing about the Kiva acquisition over the past four years. On rare occasions, Bezos shares tidbits of his other robot-adjacent operations. In 2014, he said Amazon's drone fleet is on its 10th or 11th iteration. In June, the CEO divulged that Amazon has been working on artificial intelligence for four years and now devotes more than 1,000 staffers to it. "It's probably hard to overstate how big of an impact it's going to have on society over next 20 years," he said.

Earlier this year, Amazon renamed Kiva: The newly christened Amazon Robotics team is searching for a head of robotics to help build a "new robotic platform," according to an Amazon job posting on LinkedIn.

The humans most at risk

As promising as all this technology may be, robots aren’t going to do away with human-run warehouses entirely—not yet, anyway. The flesh-and-blood variety is still considered better for high-value work like making sure the right product goes in the right box.

Some of the new systems can pluck products off shelves, such as one made by Pittsburgh-based IAM Robotics. It uses an autonomous vehicle topped with a swiveling arm that grabs items as small as a pillbox, using a suction cup. Even this approach requires a human being to carefully stock shelves so the robot's selection is precise, said Dean Starovasnik, practice director for distribution engineering design at supply chain consulting firm Peach State Integrated Technologies.

About half the human labor in warehouses slogs away on simple, arduous tasks that involve moving stuff around—doing work that's the equivalent of restocking shelves in a grocery store. It's strenuous work, with employees often walking more than a dozen miles a day as part of their job. As new robots become available, particularly to e-commerce warehouses with vast inventories and complex packing operations, these are the people whose jobs will be most at risk.

No comments:

Post a Comment