Take two Butterfingers and call me in the morning.

Nestlé is by far the largest food company in the world. Its 335,000 employees produce more than 2,000 brands, manufactured in 436 factories across 85 countries. It’s Europe’s most valuable corporation, worth $240 billion, comfortably more than oil giant Royal Dutch Shell. Among the world’s 195 nations, it sells in 189.

Nestlé’s impact on the history of how we eat is almost impossible to overstate. Sweets as we know them wouldn’t exist without Henri Nestlé, the company’s founder, who in the late 19th century supplied condensed milk for the world’s first milk chocolate, made by a neighbor in Vevey, Switzerland. Nestlé scientists created the first instant coffee, Nescafé, just in time for World War II rations. Nestlé chocolate was in the first chocolate chip cookie.

The Nestlé food and drink empire, including San Pellegrino water and Stouffer’s frozen dinners, is built on a foundation of sugar. Butterfinger, Cookie Crisp, KitKat, and Oh Henry! are all Nestlé products. So are Drumstick sundae cones, Häagen-Dazs ice cream, and Nesquik chocolate milk. In 1988, Nestlé even bought the life-imitates-art candy brand that makes Laffy Taffy and Nerds: Willy Wonka.

Nestlé headquarters in Vevey, Switzerland.

The company’s headquarters, on Vevey’s Avenue Nestlé, is far from a psychedelic sugarscape out of Roald Dahl. The building, the biggest in town, is a high-modernist pile of aluminum and green-tinted glass that resembles an upscale hospital or a midsize intelligence agency. Up a spiral staircase of gleaming metal, offices have fairy-tale views of sparkling Lake Geneva and the mist-shrouded Alps beyond. The perspective testifies that for a century and a half, sugar has been sweet. It isn’t anymore. Sugar is joining tobacco and alcohol in the club of products in which governments have taken an interest. In March the U.K. followed Mexico in imposing a tax on sugary drinks in an effort to cut obesity. Saudi Arabia may follow. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is weighing far tougher rules for sugar labeling, and the latest edition of U.S. dietary recommendations contained the strictest guidance on sugar yet.

In a 2013 review of published research, scientists affiliated with France’s national scientific institute wrote that sugar and sweets “can not only substitute [for] addictive drugs, like cocaine, but can even be more rewarding and attractive.” Although sugar is “clearly not as behaviorally and psychologically toxic,” cravings for it can be just as intense, they said.

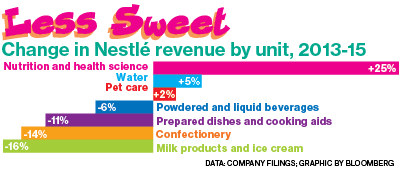

Sales in Nestlé’s confectionery business have fallen every year since 2012, matching declines of competitors. After assaults on sodium and saturated fats, some industry figures are wondering openly if Big Food is the next Big Tobacco, with all the destruction of value that would imply. At major food companies, “there’s complete paranoia,” says Lawrence Hutter, a consultant at Alvarez & Marsal in London who works with them. All the large food producers say they’re trying to reduce their financial dependence on sugar. In fleeing the storm, they’ve darted for varying types of cover. Coca-Cola has shrunk soda cans; Mondelēz International, the maker of Oreos, has become a power in the gluten-free movement; PepsiCo has tried shifting toward healthy-ish snacks such as hummus.

Nestlé has chosen a radically different path. It wants to invent and sell medicine. The products Nestlé wants to create would be based on ingredients derived from food and delivered as an appealing snack, not a pill, drawing on the company’s expertise in the dark arts of engineering food for looks, taste, and texture. Some would require a prescription, some would be over-the-counter, and some are already on store shelves today.

Nestlé’s goal is to redefine itself as a scientifically driven “nutrition, health, and wellness company,” the kind that can thrive in a world where regulators may look at Butterfingers not so differently from Benson & Hedges. If this vision is realized, a visit to the family doctor in a decade’s time might end with a prescription for a tasty Nestlé shake for heart trouble or a recommendation for an FDA-approved tea to strengthen aging joints. The company would expand from the vending machine and supermarket to the pharmacy, doctor’s office, and hospital. At the same time, it would keep its core food and sweets businesses. In other words, Nestlé would sell a problem with one hand and a remedy with the other.

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, May 9 - 15, 2016

Ed Baetge doesn’t touch any of Nestlé’s candy himself, except for a bit of dark chocolate from the high-end Cailler line, and even that only on the weekends. Nor does he much fit the template of the colorless Swiss company man. Next to his desk are a surfing calendar and a framed photo of a cobalt-blue wave cresting off Torrey Pines State Beach north of San Diego, where he grew up and still bodysurfs whenever he gets back to the U.S. When he makes a joke, he throws his head back into an earsplitting laugh and, a beat or two later, draws his hands into a single wide clap. In the land of the world’s finest timepieces, he wears a Mickey Mouse watch.

Baetge, 59, was hired in 2010 to run the newly formed Nestlé Institute of Health Sciences. His pharmaceutical bona fides are unimpeachable. After earning a Ph.D. in molecular neurobiology at Cornell in 1983, he worked at a series of biotech companies. He spent 2001 to 2010 at ViaCyte in San Diego, working on treatments for diabetes. When Nestlé came calling, asking Baetge to lead research into how food could be turned into marketable therapies, he was considering an offer to run a New York center for stem cell research, one of the sexiest areas of contemporary science. His medical colleagues were shocked when he said yes to Big Chocolate. “I was, like, in the hot seat for stem cells,” Baetge says. “They’d go, ‘You’re going from there to work on nutrition?’ ” Nestlé gave Baetge a 10-year budget of 500 million Swiss francs ($524 million).

Today, Baetge works in a narrow office, beneath an electronic whiteboard crammed with scribbled red notes, in Lausanne, a short drive up the lake from Vevey. On his desk are a Swiss army knife, bags of granola, and a half-dozen pill bottles. He’s collecting supplements such as cat’s-claw, a Peruvian vine purported to have antiviral properties, to test whether there’s anything to the claims.

More than 160 scientists from cell biology, gastrointestinal medicine, genomics, and other fields work for Baetge in two buildings here. One lab, on the scale of a child’s bedroom, is kept in near-permanent twilight so light-sensitive dyes can illuminate microscopic muscle fibers and the nerves that control them. In samples of young muscle, the nerves glow candy-apple red and connect to each fiber in tight circles of electric green. As tissue ages, the nerves turn spindly and faded. The more irregular the green, the worse the interface and control of the muscle—meaning more falls, weakness, and general decrepitude.

A second room, devoted to the brain, contains a laser-powered microscope the size and color of a small barbecue grill. Its job is to record, as often as 4,000 times a second, the activity of individual brain cells on lab slides. Healthy neurons, displayed in bubble-gum pink on a nearby monitor, are electrical dynamos that fire a never-ending cascade of signals. Researchers here are studying Alzheimer’s disease, which strangles neurons, blocking the links that allow the brain to function. Slowly those neurons go dark. No drug has managed to halt the progression.

Baetge argues that food could be the basis for an entirely new type of medication—both preventive treatments and therapies for acute disease. Drugs delivered as foodstuffs might, in his telling, blunt the impact of aging, ease the symptoms of chronic illnesses such as diabetes, and even slow declines in cognition. Food is cheap, plentiful, and familiar. It “really turns the pharmaceutical model on its head,” he says. “How do we activate the biggest drug that we take every day?”

Much of what’s being done at the institute is “just like pharma,” Baetge says. “They’re screening new chemical entities, and we’re screening natural products, especially ones that come from food,” such as extracts or purified molecules from mushrooms, tomatoes, and other plants. His team has built a library of more than 40,000 such compounds to try.

One dream achievement is personalization, using data on an individual’s diet and health history to design bespoke suites of agents that could be delivered in a capsule—imagine a Nespresso pod, perhaps, but for high cholesterol. Baetge also has the use of an array of gleaming genetic sequencing machines. Understanding the genetic factors that make some people lose or gain weight could allow Nestlé to sell slimming plans customized to an individual consumer’s genotype.

Greg Behar is another Nestlé executive who doesn’t eat too many KitKats. A champion swimmer who averages 20,000 steps a day on his Jawbone fitness tracker, he heads Nestlé Health Science, a subsidiary created alongside Baetge’s pure research arm and intended to commercialize its discoveries. Behar has a staff of more than 3,000 and a directive to develop “a new industry between food and pharmaceuticals.” The group has bought stakes in startups such as Accera, in Boulder, Colo., which makes a powdered shake it says may benefit people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Behar says Nestlé Health Science has the potential to be a business with 10 billion francs in annual revenue. Even at the world’s biggest food company, that’s a lot. Confectionery sales totaled about 9 billion francs last year; an additional 15 billion came from milk products and ice cream; and powdered and liquid beverages, particularly coffee, accounted for about 19 billion.

Although research at Baetge’s institute hasn’t yet led to any actual products—something executives say will soon change—Nestlé Health Science has a stable of brands from its acquisitions and its own development work. The division already has about 2 billion francs of revenue per year from dozens of existing products. Among them are Betaquik, a milklike drink for people with epilepsy, among other conditions, and Meritene Regenervis, a flavored drink mix for fatigue and muscle function. For cancer patients, it sells Resource Support Plus, a high-protein drink available in soft vanilla and plum-mango. For the obese there’s Optifast, a line of shakes, soups, and snack bars intended to be taken under the supervision of a doctor. Some of the products are regulated as “medical foods” by the FDA.

Behar, 46, joined Nestlé in 2014 from German pharma giant Boehringer Ingelheim. Sipping a bottle of Vittel water (another company brand), he happily lays out his workout routine. He trains for at least an hour every morning, hitting the pool at 6 a.m. and biking more than 180 miles a week. He competes in seven or eight triathlons a year, and he holds the Swiss record for his age group in the 200-meter backstroke. He was one of the first adopters of the Jawbone band, in part because his brother is Yves Béhar, the industrial designer responsible for its look. Ever on message, he credits some of his vitality to a daily shot of Regenervis. “It’s just a sachet, and you mix it with water,” he says. “It’s a much better feeling than taking a pill.”

Behar says many more products are on the way, for mobility, gastrointestinal health, and the brain, among other areas. Probiotics, or so-called good bacteria for the gut, and mixes of proteins and vitamins for joints and bones are areas of focus. A final-stage clinical trial is planned on a “food-based treatment” for Crohn’s disease. There will also be “innovation fairly quickly in cognitive function: memory, mood, anxiety. In these areas we are right now developing products,” he says.

For the most part, the concepts Nestlé is working on won’t appear in the marketplace as, say, a few extra ingredients in a Crunch bar. “If you find something really breakthrough and just sprinkle it in your yogurt, good luck getting a few more cents for it,” says Wolfgang Reichenberger, a former Nestlé chief financial officer. He’s now at Inventages, a venture capital fund focused on the junction of food and health, in which Nestlé is a major investor. Instead, Nestlé plans to sell its developments primarily as standalone medical products, which command higher margins and face less competition than supermarket foods.

If making consumers fat has been big business, making them healthy could be bigger. The pharmaceutical industry is worth $1 trillion a year and growing. Despite the scale of the potential rewards, the financial world isn’t quite sure what to make of Nestlé’s categorical leap. Introducing an in-depth report on the transformation in January, consumer analysts at France’s Exane BNP Paribas said they “are not pharma experts” and needed to bone up on the business with colleagues. The next month, Credit Suisse analysts fretted that Nestlé could be straying too far from its core, with little clarity on how competitive it will be “should Big Pharma choose to lock horns.”

That assumes Nestlé can even get its new products past government agencies. The fuzzy border of food and drugs, taking in ill-defined categories such as “functional foods” and “nutraceuticals,” is dominated by pseudoscientific supplements of dubious health benefit, often just a step ahead of regulators. In 2013 the FDA warned Accera, one of Nestlé’s new partners, that it considered the company’s Axona drink to be an “unapproved new drug,” giving ammunition to plaintiffs seeking a class-action suit who argued they’d been duped into thinking it would ameliorate Alzheimer’s. The suit was settled out of court; Accera says it responded to the FDA’s concerns and Axona remains available, though Accera has since turned to more traditional drug development.

Many doctors and health activists are intensely skeptical of nutritional aids of all kinds, and a company that’s essentially domiciled in Candyland might not be the ideal candidate to change their mind. After all, one of the best things many people could do for their body would be to eat far less of what Nestlé has spent more than a century selling. “We have known for decades what people should be eating to be healthy, and that’s a balanced diet of whole foods,” says Mark Schatzker, the author of The Dorito Effect, a 2015 book about the science of food. (His brother, Erik Schatzker, works for Bloomberg Television.) “When it comes to basic nutrition, magic pills and magic drinks have never worked.” He adds: “Generally speaking, the more we mess with food, the more we screw it up.”

ExxonMobil aside, it would be hard to name a corporation that’s attracted as much all-time negative attention from environmental and human-rights activists over the years as Nestlé. Beginning in the 1970s, campaigners accused the company of using overly aggressive marketing to persuade mothers to buy baby formula instead of breast-feeding. They pointed to sometimes tragic results, with mothers mixing formula with contaminated water to stretch their supply, thus sickening or killing their infants. The resulting boycotts and protests lasted into the 2000s and shaped the views of a generation of activists. More recently, Greenpeace introduced a withering campaign that accused Nestlé of contributing to the destruction of rain forests, and the animals living in them, by buying from unscrupulous palm oil plantations. A viral video showed a KitKat wrapper being opened to reveal an orangutan’s severed finger, and protesters infiltrated the company’s 2010 annual general meeting, hiding in the rafters to unfurl banners.

Now, Nestlé says it believes “breast milk is the ideal food for newborns and infants” and that it conforms to World Health Organization guidelines on formula marketing; it also agreed to stop buying palm oil from plantations linked to deforestation. Wanting to be seen as a more responsible actor, Chief Executive Officer Paul Bulcke has set a variety of objectives in categories such as reducing carbon emissions, increasing the welfare of farmers, and conserving water. The effort is backed by an extensive public-relations campaign, and an annual progress report, Creating Shared Value, runs to more than 300 pages.

The company’s clear preoccupation, though, is with rebutting the charge of complicity in soaring obesity rates. Nestlé says it’s gradually reducing sugar, salt, and saturated fat where it can and trying to help children learn “to balance good nutrition with an active lifestyle.” It’s rolled out lower-sugar versions of cereals such as Cheerios, and some boxes of Smarties are separated into three cardboard compartments of 15 candies each to nudge consumers toward eating less.

Nestlé’s health efforts will still have to contend with a jumbo tub of skepticism filled to the brim by past battles. “I cannot believe there’s any food product that really improves health,” says Naveed Sattar, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow, who’s tried to measure the health effects of ingredients claimed to have disease-fighting properties. Instead, Sattar says, the most surefire way to ameliorate many serious public-health challenges would be for people simply to eat a lot less. That, of course, translates directly into money lost for food companies.

Eager to show there’s a solid basis for its ideas, Nestlé has built a 33,000-square-foot suite for human clinical trials in Lausanne, decorated in a minimalist style that calls to mind a Scandinavian airport terminal; it was certified as a health facility by the local authorities. It’s run by Maurice Beaumont, a jovial former French Air Force doctor who studied slow-release caffeine for military pilots. (One of the challenges was delivering a decent jolt without too much of a diuretic effect in bathroom-free cockpits.) He’s particularly proud of a homemade “indirect calorimeter,” a gadget that looks like a pool lounger encased in Plexiglas, festooned with valves and sensors, and measures the energy burn and oxygen consumption of the typically overweight person inside.

The irony of Nestlé studying obesity remedies is about as subtle as the glucose load of Nesquik cereal, which has 25 grams of sugar in a 100-gram serving. Although the company’s efforts are commendable, it’s “selling products on one side that might contribute to these illnesses,” says Leith Greenslade, head of the nongovernmental organization JustActions. “On the other side, they’re finding treatments for these illnesses. Some might call that a conflict of interest.”

Stefan Catsicas is the elegant embodiment of Nestlé’s conviction that there’s no conflict. A quadrilingual Swiss neuroscientist who became chief technology officer in 2013 after a career in pharma and academia, his office in Vevey drips with good taste. A triptych of abstract color-block paintings faces a meeting table laden with Nespresso-branded chocolates and bottles of Vittel and San Pellegrino. There’s a single purple orchid and, on the floor, a gift bag of Cailler chocolate. On a spectacularly sunny Friday morning, Catsicas wears a blue-and-white-checked shirt with a blue tie, navy blazer, and gray trousers. His lightly accented English is crisp, and his media training impeccable.

“Sugar is not addictive,” Catsicas says. “You get habituated to sugar, which is not being addicted.” Shortly after he came to Nestlé, Catsicas gradually put less sugar in his morning coffee, cutting out about 10 percent at a time. Within three months, he says proudly, he was taking it black. In an hourlong disquisition on Nestlé’s efforts to make its core products healthier while also venturing into medicine, Catsicas says the company badly wants to “be part of the solution” to obesity. That desire, he argues, reflects evolving scientific understanding. “Ten years ago, my predecessor could have said we didn’t really know” about the scale of the problem, he says. Now, “everybody knows that there is an issue.”

Who knew what and when may be a subject of more than academic concern. “If a class-action group of lawyers can determine that food companies have known just how toxic sugar levels are, they will do what they’ve done to the tobacco industry,” says Peter Jones, a nutritional scientist at the University of Manitoba.

Catsicas rejects the comparison to cigarettes, swiftly countering that although there’s no such thing as a safe cigarette, there’s certainly safe food. In his narrative, even though Big Food needs to do better, it’s been unfairly tarred with responsibility in a complex debate over diet, exercise, and lifestyle. Besides, he says, it’s ultimately up to individuals to make healthy choices. And if they should happen to get sick, Nestlé wants to be there for them.

No comments:

Post a Comment